How Communes Lost Control of The Rental Game

This four-part series takes a closer look at how Luxembourg’s growing room rental market is reshaping our neighbourhoods, and what it means for the quality of life and the future of community life.

1. The Policy Gap: Regulate the Hedge, Ignore the Hostel?

The interesting thing is: on paper, the problem shouldn’t exist at all.

Luxembourg has rules. There’s a law. There are regulations. Minimum square metres per person, hygiene standards, safety requirements, registration obligations. All nicely written down, neatly printed, properly filed.

But here’s the catch: laws only work when someone checks.

And if no one’s particularly eager to enforce those rules, if the inspection capacity of the commune consists of one overworked staff member and an excel list gathering dust, then those beautiful regulations remain exactly where they started: on paper.

Meanwhile, landlords play the game with the creativity of a tax consultant in Panama.

• Register the house as a single-family home (because technically, it is).

• Omit the small detail about the six rooms rented separately (because why make life complicated?).

• Let the tenants work out their own pecking order for the bathroom queue.

• Count on the commune not asking too many questions.

And very often, the commune doesn’t.

Not because the mayors and councils want to see their villages hollowed out into rotating-door rental machines. But because the tools to prevent it are blunt, the political appetite for conflict is low, and the preferred strategy is “if no one complains, maybe it’s not happening.”

It’s a stunning approach, really - like refusing to check smoke alarms because the building hasn’t caught fire yet.

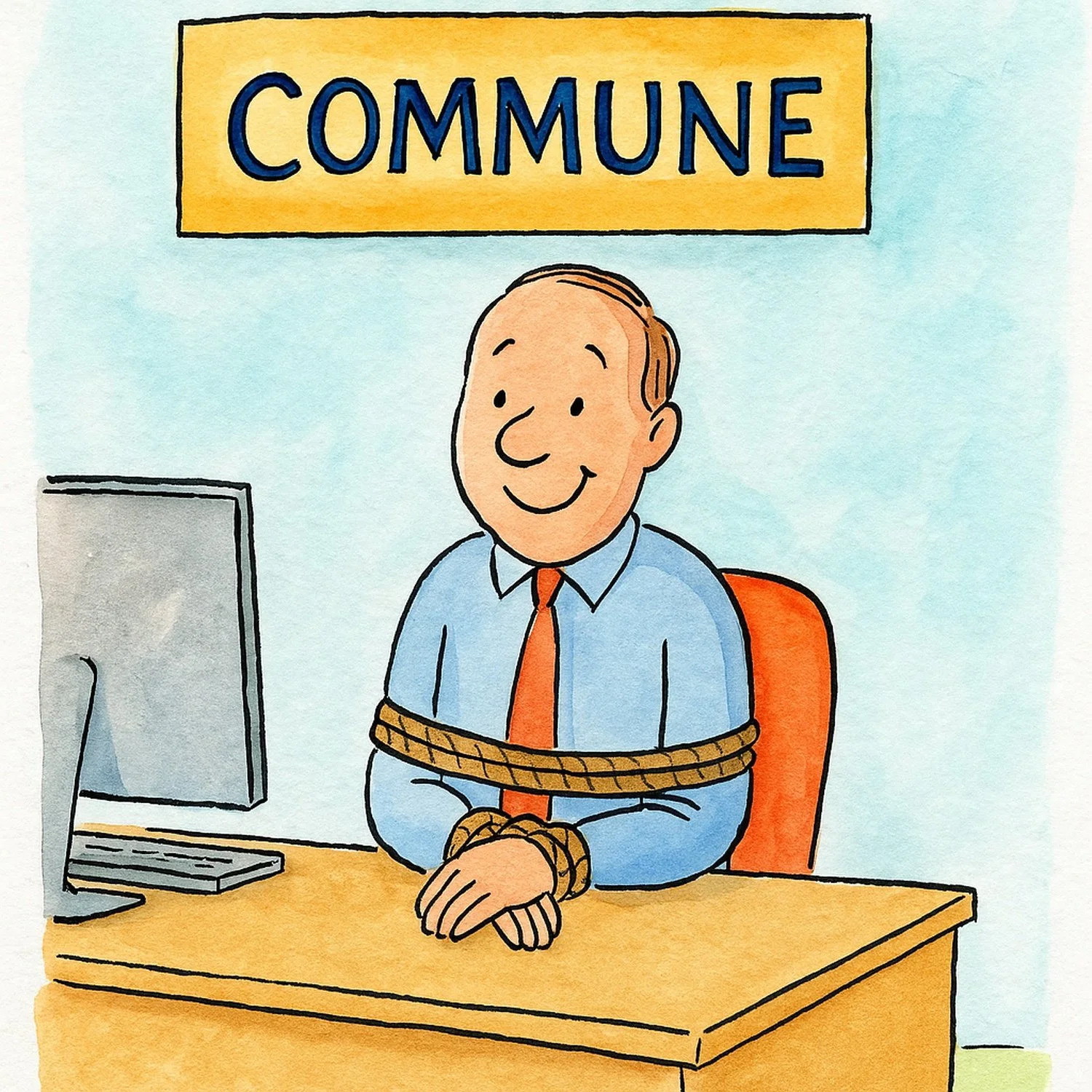

Even in communes where concern exists, where officials quietly admit that this model could wreck the character of their neighbourhoods, the fallback excuse is almost always the same:

“Our hands are tied.”

And to be fair, they’re not entirely wrong. The national law does leave some generous grey zones. Unless a property crosses into an official “change of use”, say, converting into classified multi-unit housing, enforcement gets tricky. Add to that the fact that tenants themselves may be reluctant to complain (especially if they’re unsure of their rights or their status), and voilà: the perfect regulatory blind spot.

The result? Most communes operate in reactive mode. Wait for the neighbours to get angry. Hope for the best. Respond when the noise gets too loud - literally and politically.

No proactive caps on rentable rooms per property. No serious checks on parking feasibility. No regular spot inspections to see what’s really happening behind the neatly painted façades.

It’s not about being against colocation.

It’s about being against chaos.

Because if the commune can tell you exactly how high your fence should be and what colour your shutters mustn’t be, surely it should be able to tell you how many unrelated people are allowed to share a bathroom in house intended to be a one-family home.

2. But It’s Affordable Housing! (Or Is It?)

Now, to be fair, there’s always that one argument:

“But isn’t this exactly what we need right now? Affordable housing! Shared living! A flexible solution for people who can’t afford Luxembourg’s insane rental prices!”

It’s a seductive line. It sounds caring. Progressive. Almost noble.

But let’s take a moment to unpack the reality behind the buzzwords.

Because in practice, the “colocation / Cafe zemmeren model” rarely delivers anything resembling affordability, and certainly not dignity. These aren’t friendly flatshares with agreed house rules and communal fondue nights.

They’re overcrowded rooms rented out at eye-watering prices to whoever is desperate enough to say yes.

The going rate? Somewhere between €800 and €1,200 per month. Per person. For a bedroom. Sometimes shared, sometimes with just enough space for a mattress and a suitcase. Sometimes with a mini fridge if you’re lucky, sometimes with the privilege of queueing for the one bathroom alongside seven others.

By the time the so-called “all-inclusive service charges” are tacked on, i.e. electricity, cleaning (if any), Wi-Fi - many tenants end up paying not far off what they could get a small apartment for across the border.

And over there, the toilet is likely to be your own.

Still, the rooms get filled. Not because they’re affordable. But because Luxembourg’s housing market leaves a lot of people with no real choice.

• Temporary workers.

• Seasonal staff.

• People between jobs, between leases, between options.

• Those new to the country, still collecting the golden paperwork: work contract, three payslips, and that magical garantie bancaire.

It’s not affordable housing. It’s housing as last resort, wrapped in the glossy language of “flexibility.”

Let’s call it what it is: monetising the housing crisis.

Like all business models that rely on desperation, it works best when regulation is vague, oversight is absent, and the risk of anyone asking questions stays low.

Because real affordable housing requires structure. Safety. Oversight. Not just four walls and a price per square metre that makes your eyes water.

This? This is something else entirely.

Still curious? The story continues in [Part IV →]

If you’d like to share your thoughts or personal experiences, I would be happy to hear from you.

written by Helen M. Krauss